Hello Friends,

This week we’ll be diving with falcons in precarious places. I’ve also included drone footage of the moody and marvellous location high in the Welsh hills.

If you’re a paid subscriber you’ll have received a mid-week post about those strange and equally precarious wooden buildings which still survive here in the borderland. Next Wednesday, in the second instalment of On Making, I’ll be taking a look at one of Georgia O’Keefe’s desert paintings. I’m more than a little obsessed with her work.

There’s an audio version of this post for paid subscribers - just scroll to the bottom of the page to access.

This post includes short drone footage of the very special place I’ve written about. If you want to view it you’ll need to read via the Substack app.

Hope you enjoy this week’s story,

J

It’s the barest, most bitten back place I know. Ireland Moor overlooks the Bachawy valley in Radnorshire. It’s a cluster of whaleback hills forming an undulating ridge which runs along an east-west axis, terminating with high cliffs plunging down to the River Wye. The views are spectacular, with the Black Mountains to the south, the Brecon Beacons to the west and Brechfa Forest to the north. But the place itself is a cold ghost. You feel as if you’re being watched, and you certainly are.

Walk along the rutted dirt track which bisects the moor for a few miles, heather on either side, no trees, the occasional mawn pool reflecting a mournful sky. If it’s summer and you’re lucky you might spot a curlew; if not, a red kite or buzzard. Occasionally you’ll flush the focus of this vast moor: a grouse. Mostly you’ll encounter nothing at all, though you’ll pass places with names that tell you what they once were, names like the Dancing Ground. Perhaps this wasn’t always such a lonely place.

There’s one geological feature here which seems very out of place, a high cliff which suddenly protrudes from a dip in the moor. The cliff is formed from mudstone, soft and brittle, you can pull it away and crumble it with your fingers. The erosion of the stone has formed precarious, leaning towers and pitted outcrops too dangerous to climb or stand on. Here and there stunted rowan trees entwine with the stone and manage to hold on. The cliff faces east, sheltered from the predominant winds. A good place for peregrine falcons.

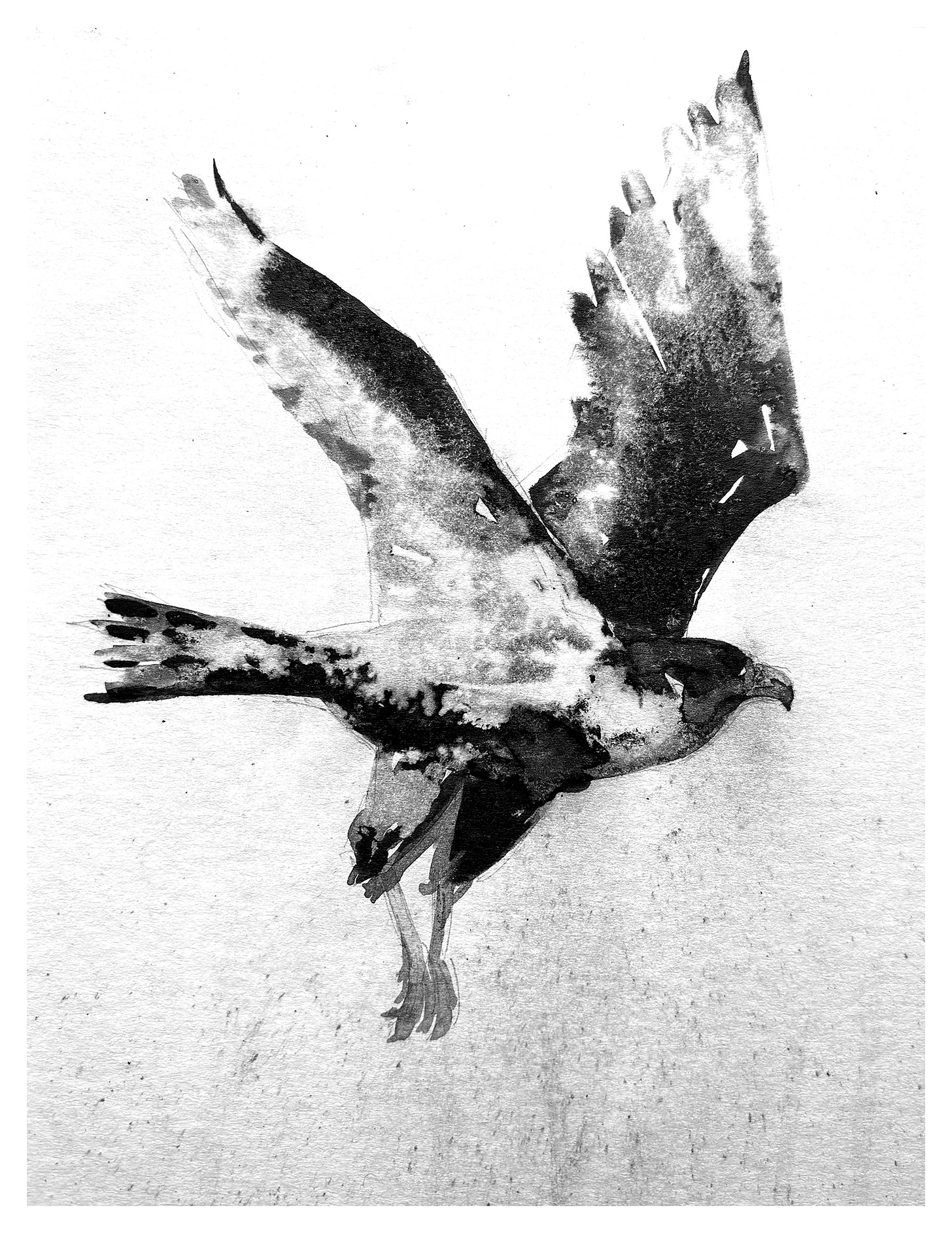

Some sounds belong to specific places. The high-pitched scream of the peregrine belongs here, as if this is the place where the falcon developed its language, against the ricocheting walls and hanging sky. I once saw a peregrine perched on the steeple of a church in the middle of a large town and watched it slide into the air above the rooftops to attempt a meal from a flock of pigeons. They circled over my workplace while the black masked assassin switched and glistered above them. It wasn’t successful that time, the pigeons flying low, just above the cars and shop fronts, too close to civilisation for the wild thing’s taste. I heard it shriek just once and in that instant the cushioned office with its polished indoor plants, Ikea desks and cheery wall decorations, fell away, crashed down, and my world was a vast, ululating sky. But to hear a peregrine in a place like that was strange indeed. Move that church steeple onto a mountain crag, break its spire into fangs, soak it for 4 seasons in storms, wrap smoke and mist around it, and then you’d have a nesting place for a falcon.

I can’t remember when I first came across the peregrines on the moor, but it was years ago, and every time I’ve walked there since I’ve seen them, a single pair, the female a huge, staring crone; the male a little blue razor, leaping to her shrieked commands. When she sees a human she slips her talons deeper into the rock in pure annoyance, and he triggers, scrambles, shivers across the bowl of land beneath the cliff to perch and sulk in a lone rowan half a mile away. It’s their place, not ours.

This is the route I take: I climb to the base of the cliff, a 45 degree slope filled with scree which shifts beneath your boots and pulls you down. I look for owl pellets, of which there are many, the cliffs also being a place where owls roost, though I’ve not seen one yet. Usually I’ve forgotten my binoculars. When I do have them I often climb too close to the cliff to use them. And so I rely on the male falcon to spook and show me his whereabouts. Which he usually does swiftly. I locate the glowering female, sometimes directly above me, aloof as an empress, still as a chess piece. If I’m lucky I’ll see her head swivel to look at me. If I’m really lucky she’ll throw that shriek at me, so high pitched it probably disintegrates molecules and makes atoms shiver. Loose stones loosen further, debris scatters, stones and bones descend from ledges.

The last time I was there was a late spring day and a poor, unassuming crow had built a nest in a skinny and sick looking rowan tree at the base of the scree slope. It sat terrified in its nest, its coal black eyes reflecting the sky where the blue peregrine circled.

I once saw the male falcon in a fight with a raven on the other side of the valley. Perhaps the falcon had thought a raven would make a good meal. Ravens, of course, live between worlds and cannot be eaten. The blue murderer dived and twisted, switched and arced, slalomed and scarred the air - to no avail. For every lunge the raven had an easy counter. As they fought I could hear the raven giggling. When the falcon finally gave up it split a tree with its scream and flew back to the cliffs. The raven followed it for a time, flipping upside down, showing the black moon of its backside.

I can no longer hear the high pitch scream of a peregrine, due to hearing loss. But I also can’t hear our doorbell, which makes me happy because I’m a person who's too kind to turn away salespeople and politicians. Still, I’m sad about the falcons. Often loners and edge dwellers, we creatives yearn for experiences of the sublime which will inspire the work. We seek the heights and dredge the depths. We peer from our cliffs for days on end, starving and ravenous for life. Our moods are stormy weathers. That’s how it is for me sometimes. I run to the easel to create a picture which has rushed in and needs to be pinned down before it flees. I stare, glower and rage as it takes the wrong shape, or shifts through the one that should have been fixed and moves on to something else, the images changing from instant to instant like a flock of birds I’m hanging above. I stoop, I miss, stoop, miss. Rage. I’m not saying I’m a falcon, but oh but how I dream of it!

We creatives are also often obsessives. We hang onto things far longer than we should. We’re tenacious when tenacity is the required quality, and also when it isn’t, when it’s taking us to places of starvation. We often have an unloosening grip. Many times I’ve sat on a cliff ledge with my legs dangling, staring down at the world, in a funk or fury; or sat in that same place taking in the falling light, so in love with the world I could almost grow wings. Never ever wanting to leave.

I’ve been working in the studio for 8 days straight and I’ve barely seen the mountains which are just behind the little town that’s hosting me right now. The other day a lady walked in and asked me if I knew the name of a bird she’d just seen while driving here. Like that one, she said - pointing at a picture of a red kite - but smaller, with pointed wings. It was blue-grey, very fast. A peregrine falcon, I said, and I showed her a photograph. Yes, that was it, she said. Where did you see it? I asked. Up there, she said, on the mountain, that stretch where it gets very bleak, nothing there at all.

Except falcons.

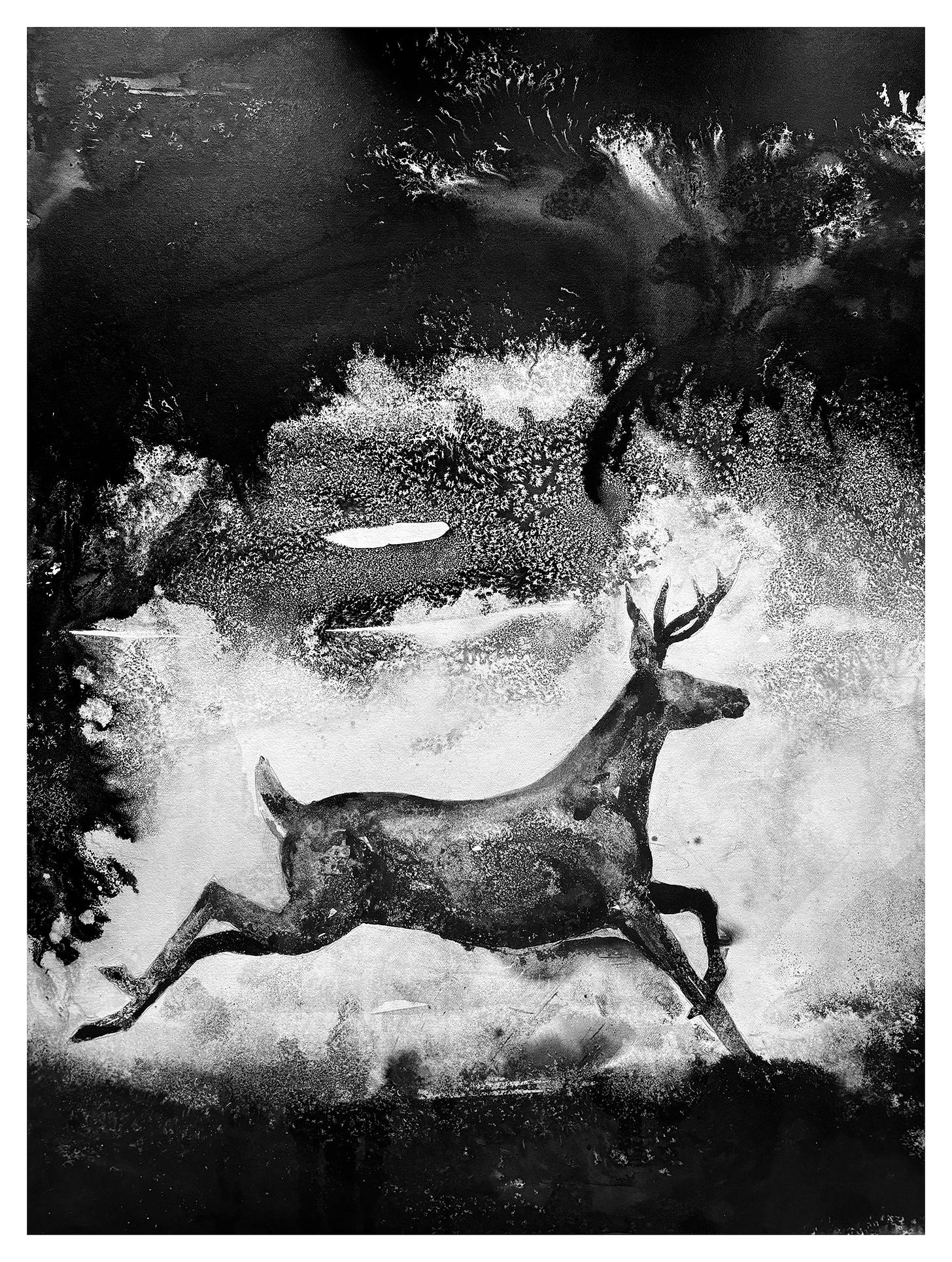

Running Deer

Click the image to see my latest print.

15% discount code for paid subscribers below

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Into the Deep Woods with James Roberts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.