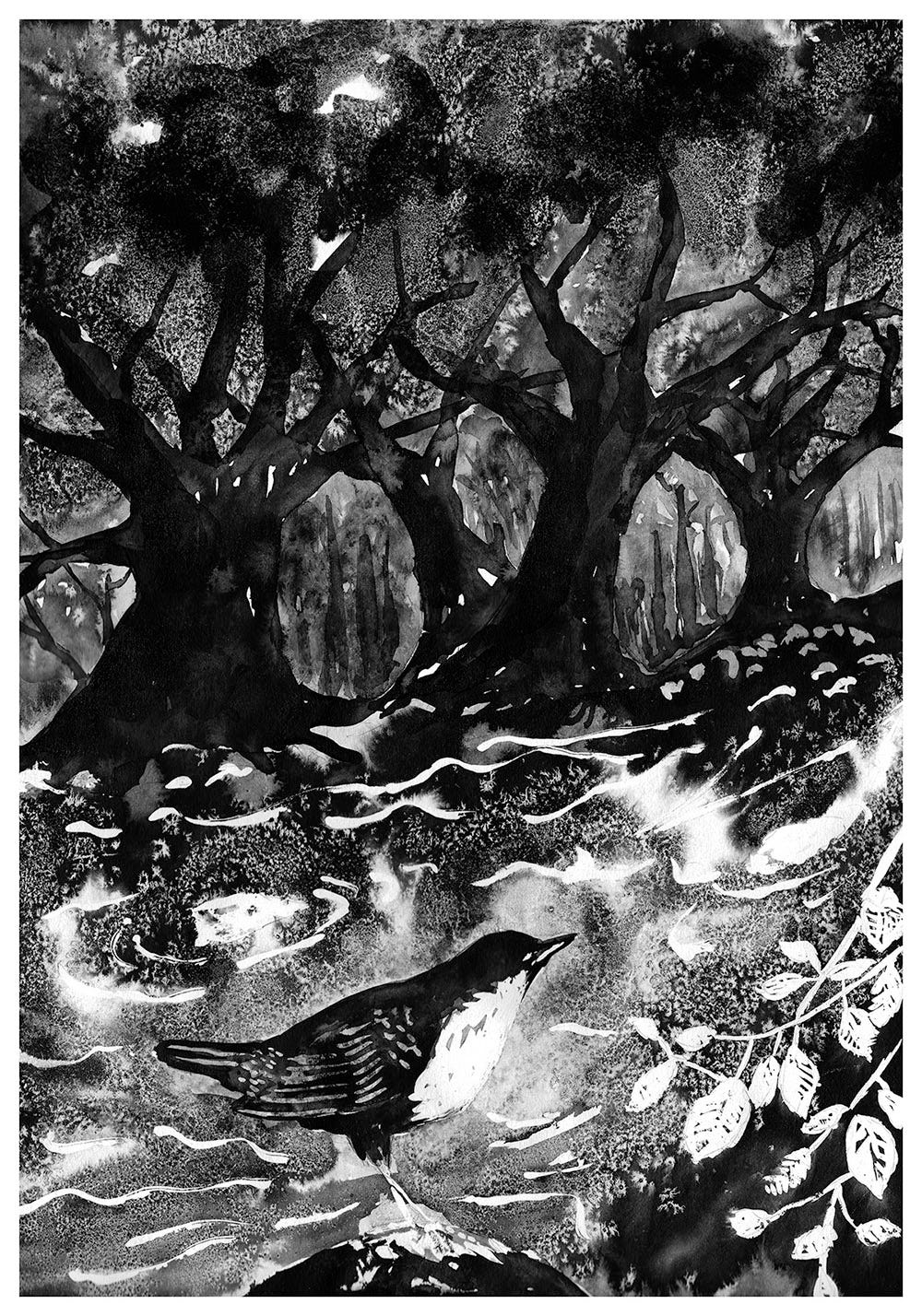

Light under leaves. At this time of year the woods are luminescent, the still new leaves not filtering but staining daylight. Everything has a cathedral interior look. It’s taken me a year to get used to this new square mile, even though it almost adjoins my old one. But this place is quite different, not the open-skied and whale-backed hills just over the border in Radnorshire, but closed in, cut from the deep woods, and seemingly about to be taken back by them, though the old forest that is long gone. Names from an older language – Worzel Wood, Yeld Wood, Benbow Wood, Hanter Hill. Mill streams, oak copses, little muddy meadows with cuckoo flowers and lazing cattle. A remnant. Years ago my sister lived in Burwash, in the High Weald of Sussex. Near her cottage, down a narrow lane, was the house where Kipling lived and where he wrote Puck of Pook’s Hill and some of his finest poems.

“You will hear the beat of a horse’s feet

And the swish of a skirt in the dew,

Steadily cantering through

The misty solitudes

As though they perfectly knew

The old lost road through the woods.

But there is no road through the woods.”

That place seemed to inhabit parallel times which intersected in the surrounding oak woods. It’s the same here. Dusk is more liminal. Moonlight casts spells. Trees seem to move around, never appearing quite where you remembered them to be.

I’ve been walking in the same wood most days since April. There are goldcrests and black caps, linnets, long-tailed tits. I’ve had several close encounters with a fox, who stares at me for a time, questioning my intentions, then bounds away over and under the brambles, across the meadow to the river. Yesterday a roosting tawny owl spooked only a few feet in front of me and fled silently into denser cover. To get to the wood you have to cross two narrow bridges, one spanning an old mill leat, the other the little river Arrow, which is more of a stream than a river. The iron bridge catches debris from the floods. Its railings are bearded with yellow reeds bent double around the metal. It stands on thick stone piles built between hazel trees. In the cracks between the stones there is now a dippers’ nest. I’m trying not to disturb them. Dippers had a bad year last year when the river level dropped too low in the drought and the normally clear water became almost opaque with algae. A starvation summer. But this nesting season has been successful so far with one brood already fledged and another on the way. I see the birds sometimes as I cross the river. More accurately I see their blurs and aftertrails as they speed downstream. Occasionally one will be standing on a stone, bobbing and bowing, then self-baptising, little devotee of the river.

Devoutness is a quality we no longer admire in these times. Individualism and self determination are what we esteem. Once we were god made, now we’re self made. The devout among us are stuck in the past, praying to false entities. The word itself has been in decline since the mid-nineteenth century and it barely features in the day-to-day lexicon of our lives. Yet there is now a requirement for a new kind of devotion, not to a god, but to the process of life, the mystery and beauty of it. A sense of the sacred in the universe is perhaps a necessity if we are to find the will to undertake the huge projects of restoration which our home planet desperately needs.

For a little while now I’ve been involved in a project to raise awareness about the condition of the streams and rivers in this area, which are in decline. As part of this I’ve talked, read, and exhibited artwork. The most memorable image for me from this time is a large painting by another artist of a riverside shingle beach with three red-cloaked figures wading into the water, giving blessings and saying prayers. Extinction Rebellion’s priestesses of the wild. I think they frighten us when we see them. There is an old power in their presence going back to the time of religious devotion. Perhaps we don’t quite believe in the irrefutability of empirical materialism.

There are humbler ways to return to the sacred. The dipper shows us how. Though winged, its world is water. It pays constant attention to the life of the river, which is its life. The dipper is submerged literally and metaphorically. The verb merge comes from the latin mergere, which meant to dip, but the word evolved to also mean to be absorbed by (or into). The dip(per) therefore becomes the river. The act of merging, submerging, or emerging is both physical and imaginal when we look at how we really live, which is through a constant process of change, of interaction with and absorption of other forms of life. We merge, like the dipper, with everything. All we have to do to recover our sense of the sacred is pay attention to that.

It is now June and the nesting dippers will soon be gone, their broods successfully reared, their nest given back to the river, for the floods to take and reconfigure downstream. There’s a rookery half a mile away, in the oaks bordering the river above the mill. Perhaps the dippers’s nest will become part of a rook’s nest, or a bed for bluebells, celandines, wood anemones. Perhaps a wading child will find it caught in the fork of a fallen branch. They’ll bend down to lift it, turn it over in their hands, stare at the little, perfectly shaped cup formed inside it, and wonder at the magic of the river and the little gods which inhabit it.