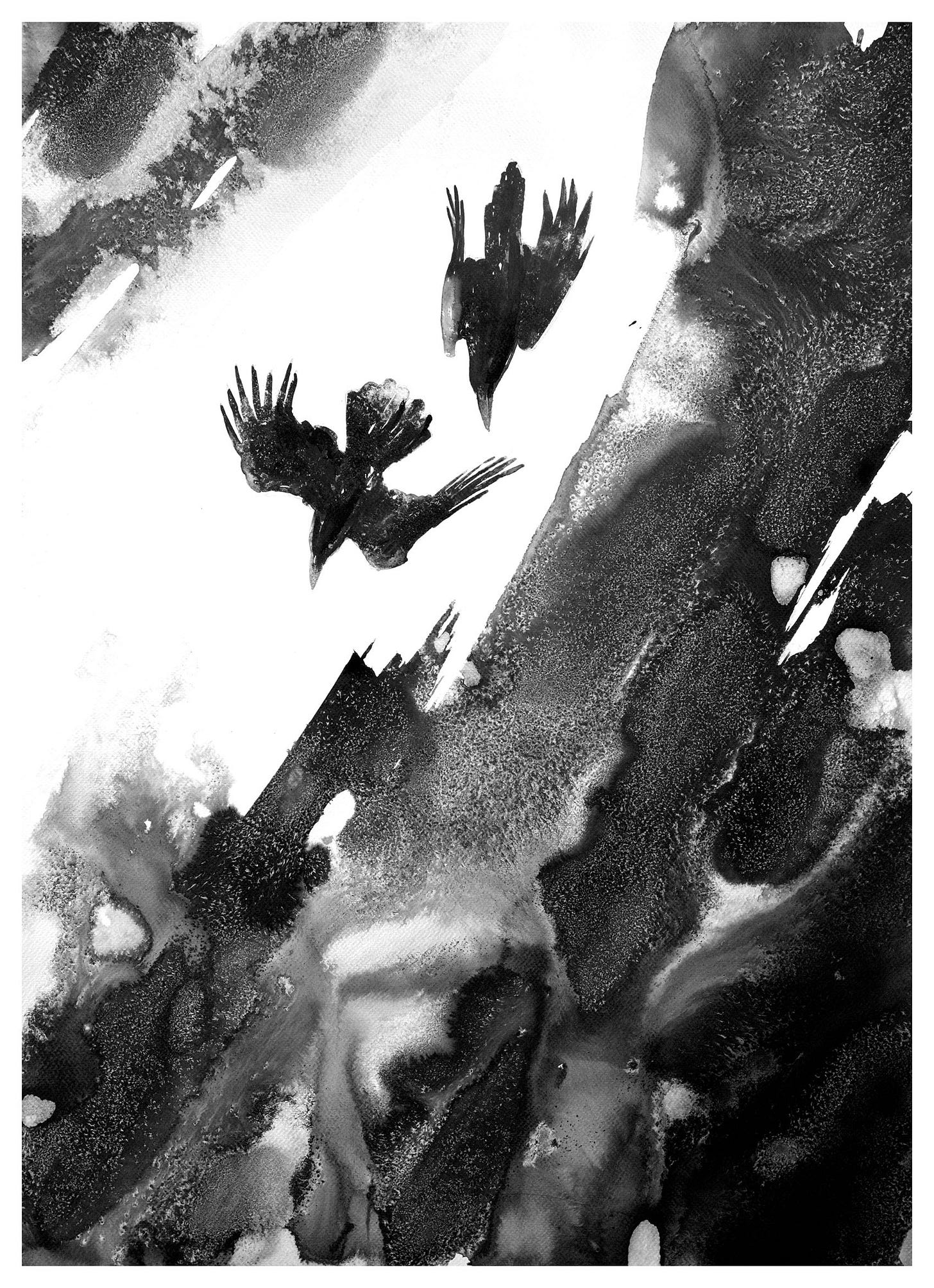

This morning the ravens were gathering, only a few at first, but more and more as I watched, coming across the valley from Radnor Forest. It must have been the wind conditions attracting them, blowing hard from the north west. On this part of the ridge the slope plunges at a steep angle, then scoops back up towards Hanter Hill, a curve like the drop between two peaks on a rollercoaster. For a raven this must mean surf’s up. I’m trying to imagine the shape of that wind, a cone of air which narrowed and accelerated as it rose, plumes and scarves blowing from the top. There must have been a down draft, a vertical chamber of wind hurtling back to the earth, because this seemed to be what the ravens were drawn to most, collecting in pairs (always in pairs) high up, then riding down, flicking from side to side, pulling their wings close then, as the stony ground approached, opening parachutes to sail off and rise again.

How I love ravens. I don’t know what I’d do without them.

Due to the direction of the wind I noticed a few different calls today, quiet sounds I’ve never heard from ravens before: purrs, murmurs and almost-whispers. Perhaps these sky rides of theirs are also mating rituals, their calls little love notes to pass as they pull out of a dive. Or perhaps they’re polite compliments to the wind, quiet conversations between turns, snatches of remembered song, guessing games - I spy with my raven eye. They’re certainly conversing.

I’m in hiding from the media at the moment. I doubt I’ll make this a permanent arrangement, but I can hope. The coverage of the war in Gaza has appalled me and I’ve come to the point where I just can’t watch or read any more. The conversations around the fighting seem to have brought us to a new low point in human interaction. I’ve never heard so much shouting, so much jostling for high ground, so many attacks, thrusts, ripostes. It’s revolting.

I remember my dad telling me once that when he was growing up, when his family relaxed in each other’s company they didn’t do much talking. Instead they sat around an old piano and sang. Sometimes they’d play card games, or watch the fire in the stove. Music and quiet. Shared space was enough - though sometimes, like the ravens, they danced.

The rooks and jackdaws that live around our house often perch silently in pairs and do absolutely nothing for hours. This quietness is a requirement of the imagination, the use of which is necessary to the soul, as important as food and air. Without it a madness starts to take hold, identified by the types of combative conversations we seem to be holding these days.

Not everywhere though, and not all the time. I watched this video conversation between Gabor Mate and Cornel West recently, which reminded me how rich conversation can be. The way they speak is almost a ritual, a passing of the cup back and forth, an honouring of each other. Though they talked about the darkness which surrounds us they projected so much light. Mate, when asked about whether he has hope for the future replies that he prefers not to think about hope, but instead about possibilities. Possibility depends on the imagination, whereas hope can defer it, or require it to be exercised by others. These wise souls also spoke about music, about the meaning of music and the music of meaning. It’s a conversation I’ll listen to again and again.

I have a terrible ear for lyrics. I’ve mangled the meaning of just about every song by hearing words which aren’t there. I’ve sung along to favourite tunes for decades using totally the wrong lyrics, often wondering why so many of them make no sense: “Are we going to scar brother hare? Pass the sage, Rose, Mary’s on time.” Etcetera. This inability has made me develop a preference for talking songs: most of Leonard Cohen, late Johnny Cash, and Benny Hill’s Ernie - the Fastest Milkman in the West, which always brings a tear to my eye. When you can’t hear words properly you tend to listen to the sounds within them, the melody, the shape of the tones and rhythms. In this aspect I’m almost pitch perfect. I can pick up any melody on a piano (slowly, one-handed). What I love about melody is its possibilities, how one group of notes played in a certain order can be transformed completely by a simple change, a drop in tempo or pitch, a slight rearrangement. These changes can shift how you feel in an instant, like all possibilities.

The best forms of play need the least material input. Music requires only the air in our lungs, the muscles of the throat, tongue and lips. Poetry, the highest literary form, needs no paper and ink, no book or screen, only breath. A child needs a space to run and jump, or somewhere to lie and look up at the clouds. The ravens just need a little wind. Out of their play a raven language is formed, which is perhaps how human language is also formed, from joyful utterances - purr and moan, whistle and hum. Our myriad languages could have been conjured by playing in places the way the ravens play with the wind-filled scoop in the ridge. There’s an orderliness to their actions: they give each other space, wait their turn, celebrate innovations, the many possibilities expressed in the dance. It’s a conversation of the best kind.

Conversation is one of those words with many branches. The Old French form meant way of living, of keeping company with, or the manner in which one conducts oneself. It specifically referred to the customs of a place. This meaning is now obsolete. It needs to be reinstated. Conversation is not just about words.

As the ravens flipped, whooshed, swooped and dived the light on their feathers continually changed. Their monotone plumage flashed silver-blue, silver-green, silver-white. As the low, late-year sun caught them again they trailed sparks of orange and yellow. Every transformation revealed different hues, colours which appeared for the first and last time, the infinity possibilities of black feathers. So too their calls, as diverse as our own. Quietly, with a little embarrassment at first, though there was not a single person on the hill but me, I called back. It was a conversation I wanted to be part of.

Found Things

I discovered the work of the Alaskan poet John Haines via the wonderful curatorship of Richard Skelton and Autumn Richardson at Corbel Stone Press. I return to his work all the time. I recently bought a book of his collected poems, The Owl in the Mask of the Dreamer, a title so rich in possibilities it has set some subterranean rhythm going in me which is producing an ongoing series of owl head (owl mask) pictures. This poem from the collection is one of the quieter pieces, but it’s a favourite. The line - Strange to be a seed, and the whole ascent still before us - is all about possibility.

The Sun on Your Shoulder

by John Haines

We lie together in the grass,

sleep awhile and wake,

look up at the cloverheads

and arrowy blades,

the pale, furred undersides

of leaves and clouds.

Strange to be a seed, and the whole

ascent still before us,

as in childhood

when everything is near

or very far,

and the crawling insect

a lesson in silence.

And maybe not again

that look as clear as water,

the sun on your shoulder

when we rise,

shaken free of the grass,

tall in the first green morning.

The collection is published by Graywolf Press and can be purchased on their website here

I have a selection of raven prints for sale on my website. You can find them here

Until next week, J

Ravens, John Haines and Benny Hill together in the same post! You are a phenomenon. Beautiful as always, and I'm heading to that YouTube conversation now.

I'm in awe. So many thanks for your sharing. Your witnessing is what I needed today. To the mystery, to the longing... The ravens here in Sudbury, Northern Ontario Canada, they fly westward each evening before nightfall. I go to the hills to join them. I hear their wings beat overhead. Some fly so close. They trickle by, then come in droves, dancing, inverting, touching wings, skirting... one by one, twos by twos, families, free, warbling, calling, responding, listening with all of their being to the world breathing, singing. It takes a good couple of hours... where do they go... where do they go... life lies in their constancy.