The little town where I live, nestled below the last high ridge on the edge of Wales, is part of the land of Offa, Saxon king of ancient Mercia. We know little about his life, but story fragments tell us that he was one of the most powerful rulers in Europe and that he built the largest earthwork on these islands. Offa’s Dyke is a still impressive structure which stretches 60 miles along the border of England and Wales. Its southern end begins a mile from my house, on high Rushock hill. It was built as a strategic fortification, a steep-sided bank and ditch which followed the contours of the hills looking west into Powys, a Welsh kingdom which was constantly attempting to regain the eastern lands which it had been pushed back from over centuries by invaders. This therefore is the edge of the edge of Mercia, a place-name which is synonymous with March or Mark - meaning borderland. To the west is the Celtic Fringe, a place of myths and mists, the edgeland of Eurasia. From the top of Offa’s Dyke you can look across this mountainous land, at the shifting shapes and colours of the peaks, at the storm clouds rolling in from the nearby sea. It’s been my home for two decades.

I’ve been thinking hard about the title of this project, trying to find words which are both a beginning and end, a jumping off point and place of return, the prism through which I intend to look at things on this journey. What I decided on in the end was a single word, an old word forged here in Mercia from the languages spoken by the first Saxons: Rima. It’s a word we no longer use, but one which only diverges by a single letter from its modern equivalent. Rima was a much used word in old English. Its current form rim still contains much of its meaning but it has been reduced. These days rim is mostly used to define the edge of a circular form, like a cup or bowl, the edge of a wheel, or a spectacle lens. Small things. But the Saxons used it widely and poetically. It was a word with chasmic depths, connected to the wild, a synonym for all kinds of edges - borders, banks, verges, cliffs, ridges, bounds, shores, coasts. Here are some of its usages:

dægrima - daybreak, the rim of day.

ǣfenrima - twilight, the rim of evening

særima - seashore, the rim of the sea

wæterima - the sea’s surface

wudurima - the border of a wood

Rima was, and still is, a word connected to the creation of art. In the time of its Saxon usage perhaps the highest form of art was the illuminated manuscript and a rima was an exquisitely decorated page border. Rima is also connected to poetry and to rhyme via its Latin root. Poetic forms are sometimes set in rimas. Terza rima is the three line verse form first used by Dante in his Divine Comedy seven hundred years ago. Since then it’s been used by Chaucer and Milton, Byron and Shelley, Larkin, Auden and Plath. There is also sesta rima (6 lines), ottava rima (8 lines), and rimas dissolutas, a French form where any number of lines may be used, but each line end must rhyme with its equivalent in the next stanza. Follow this root of the word back through Latin and Greek and we find that it’s connected not only to rhythm and rhyme but to movement and flow, proportion and symmetry, manner, disposition, even soul.

A rima is also a cleft, particularly related to the vocal cords. The rima glottidis is the gap where the air comes through the larynx, the source of the voice, the poem, the song. A rimaye is another cleft, huge in scale, a crevasse at the head of a glacier. Over its rim and through it pour fossil waters, the rains of past millennia, the rising of the seas.

Hopefully you can see why I chose Rima as my title.

You might say, geographically speaking, that the edges have gone. Every piece of land on this little planet has been mapped and recorded, uploaded and made available to view. Terra incognita - parts unknown - those words used on maps to denote unexplored areas, ceased to exist a century ago. Only the deepest seas are unmapped now, and the surfaces of other planets. The old edges have become blurred. Offa’s Dyke was once a place where people stood and peered out across a mysterious land. But these Welsh Marches, defended and fortified for centuries, became an international zone during the late Norman period, a place where people from all over Europe came to trade, settle and intermarry. The dyke, once the hardest of borders, faded to little more than an idiosyncrasy in the landscape. This is why rims and edges, coasts and shores, borders and boundaries are so fascinating, they continually shift and dissolve. They’re fading tracks of light, threads in the weave, fibres in the thread. There’s so much beauty in boundaries.

Many of us, these days, seem almost permanently on the edge of tears, of disaster and tragedy, of sense and sanity, even of life and death. Every news feed and publication shows this to be the case. We’re spiralling continually down into the depths it appears. But the opposite is also true. Are we not often on the edge of laughter, of joy, of our seats with excitement? Pleasure has edges (pleasure is edges!). Love is a border crossing. Almost three decades ago I was without a home and horribly lonely, walking up a cold and dark street in South London near midnight, when I heard laughter, saw lights and smiling faces through a fogged pub window. One of those faces had sea-rimmed smiling eyes: my future wife’s. I opened the door, crossed the threshold, and my life was transformed.

We’re always on the edge of the deep woods (the wudurima). Even in a land like this one, farmed for millennia, bitten back and bare. Britain is one of the least biodiverse countries in the world. It has no wilderness, but the wild is everywhere. The wild ignores all borders and pushes its own edges into every available space. This little town is proof with its jackdaw nested roofs, its rook filled trees, its kite and buzzard circled skies, its swift and martin swarmed summers, its dipper flitted, heron speared streams. And the edges of the wild are woven within us, in the threads of our veins, in our rimmed cells. Most of all it’s in the shores of our imaginations, whose borders grow and shrink, shape change and break open continually, like the seashore - the særima. This journey is about wild edges and edge-lands, about how they form, intertwine, merge and dissolve, how they’re never, ever fixed.

There is a very short and illuminating Youtube video showing Mary Oliver being interviewed by Coleman Barks. In it she states: so many of us spend our lives seeking the answerable, and bypassing or demeaning those things that can’t be answered, therefore denuding our lives of mystery and the pleasure of mystery. Her own work was an attempt to reverse this and it’s something I’m aiming at these days. This exploration of the edges and perhaps a little beyond is a journey towards it. I hope you’ll join me.

THE PRACTICALITIES

Stories from Rima will start dropping on 20th January.

The series will be accessible via paid subscription. It will cost slightly less monthly than a coffee and a croissant, but will last considerably longer than a caffeine and sugar rush.

Rima stories will be published fortnightly. There will also be notes, interludes and asides, reports from the edges when I’m out walking or travelling - sometimes written, sometimes filmed, sometimes shared as audio.

You’ll be able to comment on all of the pieces in the series, converse with the community and share your own stories from the edges (how I love to hear about your places - deer in your gardens, screech owls in your woods, wolves in your hills).

Paid subscribers will get access to all of the short essays I’ve published, an archive going back 10 years.

There will be free hi-res downloads of photographs and illustrations, as well as first views and discounts on my new artworks and prints.

You’ll be the first to know about my forthcoming exhibitions, readings, workshops and books.

Phew!

If you’re not interested in any of the above you’ll still get free access to my other Into the Deep Woods posts which will go out on alternate weeks, but may become more frequent/infrequent if it turns out I have more/less stamina than I currently anticipate . . .

FREE PRINTABLE FOR PAID SUBSCRIBERS

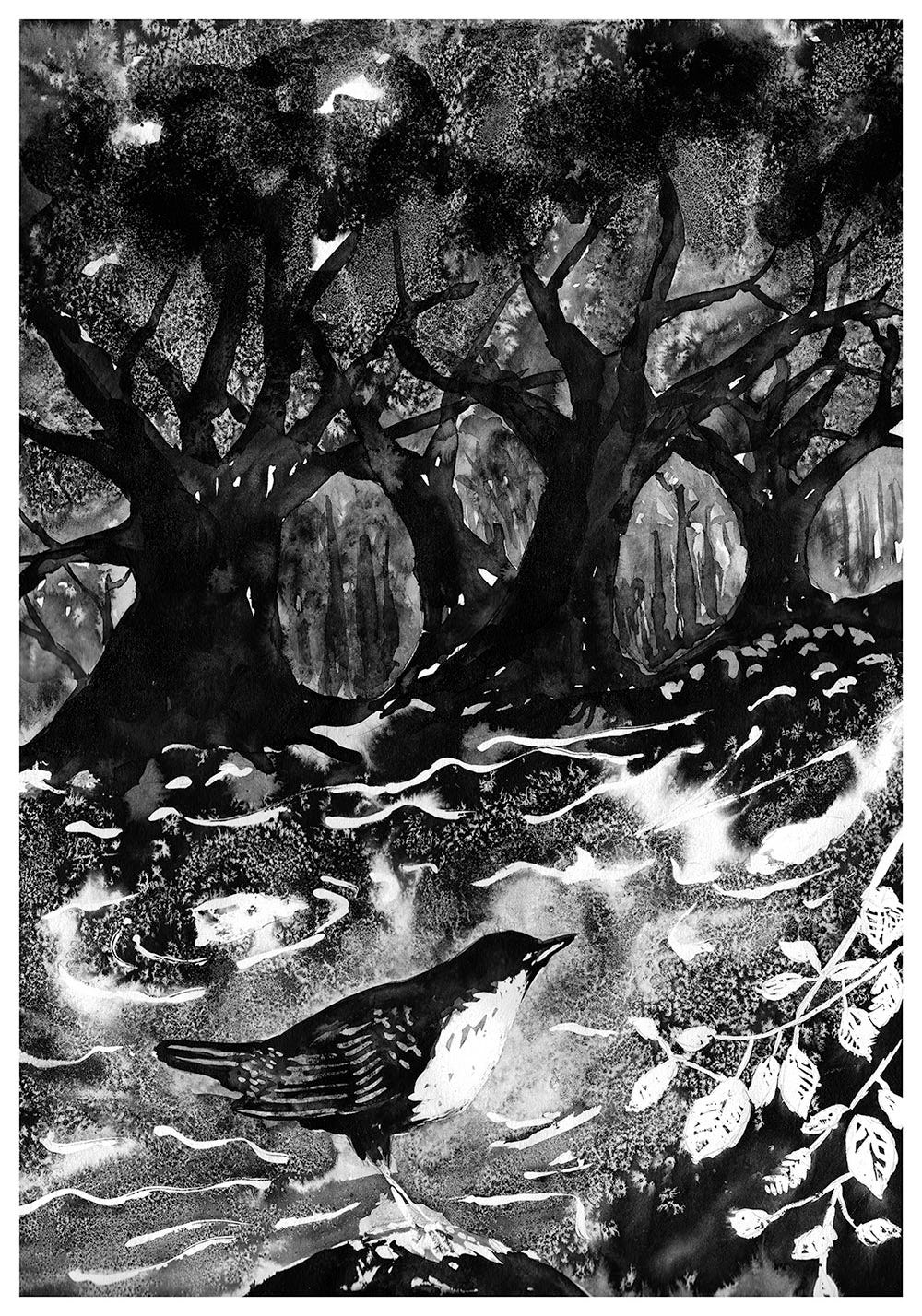

A lot of the ideas for my writing come from my artwork. I was working on this little piece last summer while I was walking a lot in a wood with a little stream where a pair of dippers were nesting under a bridge. I saw them most days, flitting above the water’s surface or bobbing on a stone. The pair were being monitored and I was told that they successfully reared two broods in 2023, after failing the year before due to flooding. So I made the picture and titled it - A Dipper in the Deep Woods. The title then worked on me for a month or two until Into the Deep Woods became the core theme and starting point for the stories published here. So it seems fitting to make this the first gift to paid subscribers, a gift from the dippers and the deep woods.

The file will contain a hi-res image which can be printed at fine art quality up to A3 size (297mm x 420mm). This can be done on a home inkjet printer. I’ll be sending a link to the file via email next week.

As an artist and writer on the edges I hugely appreciate your support as a paid or free subscriber. If you’d like to be involved with the Rima series and do not have the means to pay for it right now, please send me a message and I’ll give you a month’s access.

I’d greatly appreciate it if you’d share this email with any friends, colleagues and edge dwellers you think would be interested in this adventure.

Thank you!

J

This is the essence of great writing. Sublime, nuanced, researched, heartfelt. Can’t wait to see where you take us next on this journey.

Ha! I thought you were going to write about the artist Rima Staines ... nice article!