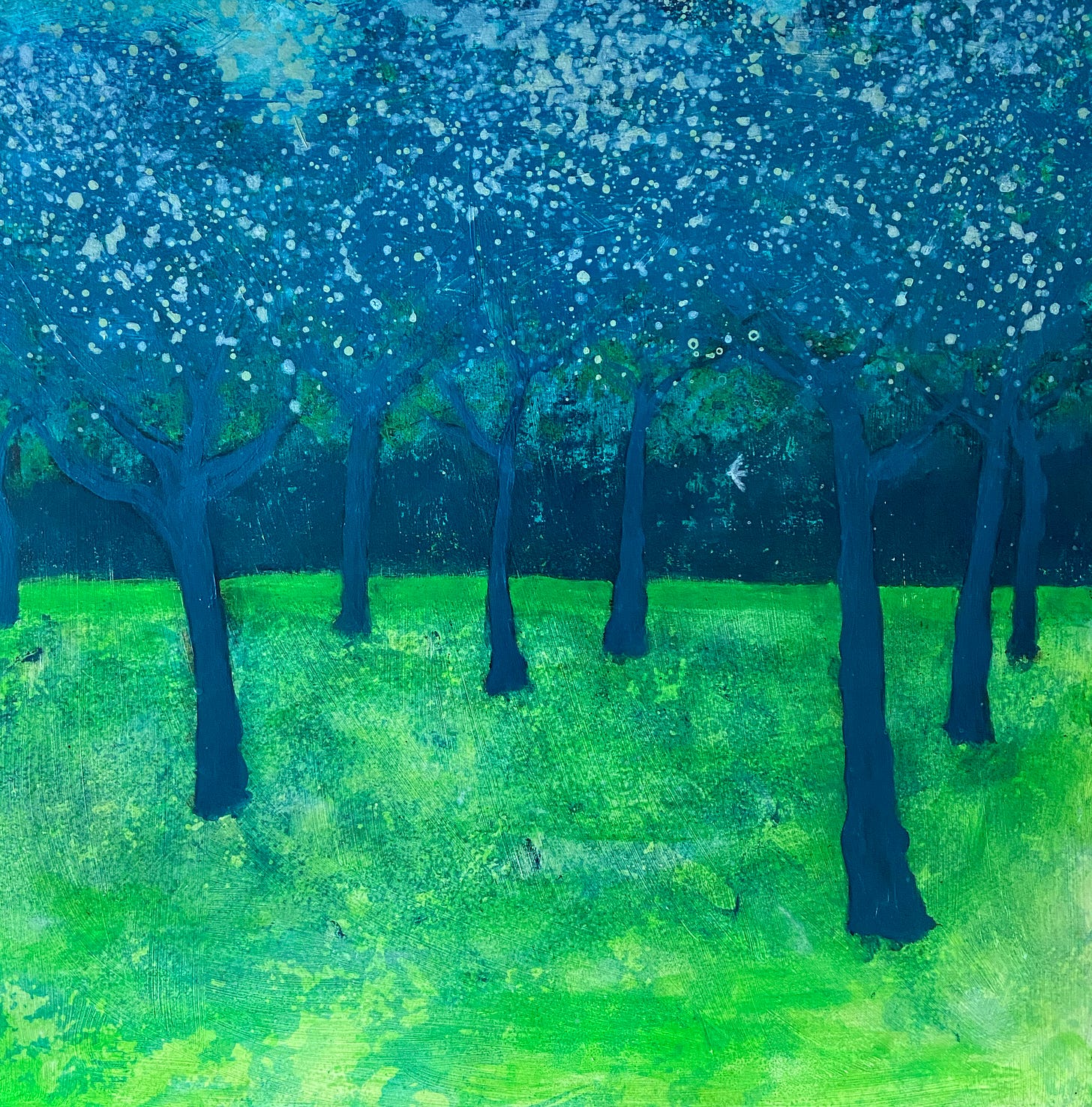

How beautiful they are

The people brushing past me

As I stroll through Gion

To the temple of Kiyomizu

On this cherry blossom moonlit night

Yosano Akiko

There is a stretch of road over the border, not far from here, which rolls and curves between acres of orchards. In late April each year it is lit on both sides with the colours of fruit blossom ranging from a…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Into the Deep Woods to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.